What kinds of questions are education reformers asking?

Part of my job as a Students for Education Reform chapter leader is to ask questions. I am constantly thinking about how to best invite people into the education reform conversation. The questions we ask have a huge impact on the answers we get.

I’ve recently been mildly obsessed with a website called Quora. I joined a couple weeks ago and have quickly added it to the list of websites I check daily. Quora was founded by Adam D’Angelo, a former engineer at Facebook. Quora allows its users to ask any question and then answer other users’ questions. The website protects against spam and the idiocy of sites like Yahoo! Answers in two ways. First, each user must have an account with a real name, typically tied to a social networking site. Second, Quora has created a currency. It costs “credits” to ask questions.

People ask questions on a variety of topics. And there are probably tens of thousands of questions already on the site.

I bring all this up because Quora is a great model for how we might begin asking the types of questions that will lead to real solutions in education reform.

The Education topic on Quora is one of the most thought-provoking on the site. Questions consider everything from curriculum to college loans to different learning styles. But there are two specific questions that stick out.

The first is this question: How can we solve the problems with public education in America? This is a great question and has generated 17 responses to date.

It’s follow-up question is interesting, though: What are some of the biggest problems with public education in America?

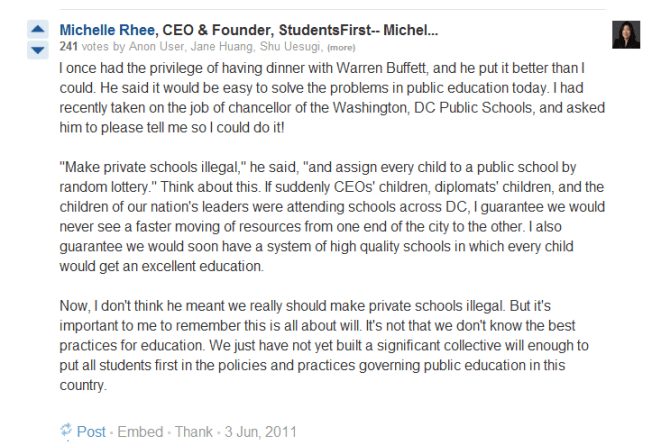

To this question there have been 31 responses, including one from Michelle Rhee, former Chancellor of DC public schools and founder and current CEO of Students First.

This answer is obviously overly simplistic, but it illuminates two major points. One, there is inequality in the education system in terms of class. And two, there is inequality in the education in terms of availability and stake-holding. If there were a diplomat’s child in every single school, you better believe that every single school would be great.

While I love this answer, I think that we should be critical of it. First, I think it’s telling that the “what’s wrong” question came after the “how can we fix it” question. Sometimes we ask the “how can we fix it” question, realize that not everyone knows what we should be fixing, and then have to ask the “what’s wrong” question. Sometimes, this is beneficial, but we need to stop taking these steps backward. What’s wrong with education? It’s not equal. Not everyone gets the same education in this country. That’s the issue.

The “what’s wrong” questions encourage buzz words. They encourage these overly simplistic answers. If we start asking the “how can we fix it” questions, we can support, fund, and develop the solutions.